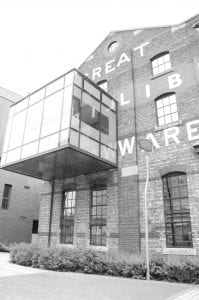

Dr Simon Obendorf from the University of Lincoln reflects on the Library building and it’s colonial past.

“The Great Central Warehouse Library building, in its site, purpose and physical structure, provides us with many opportunities to reflect on Britain’s colonial pasts. Built on a site first identified by the Romans as an ideal harbour for their “Colony on the Lindum” (Lindum Colonia – Colony by the Dark Pool), the site was used as a hub for trade across Roman Britain and out to other parts of the Roman Empire. As the United Kingdom gained – and gained from – its own Empire, the site on the Brayford was expanded and strengthened to become a key transshipment point between water-based and railway transport. In 1907, the Great Central Goods and Grain Warehouse (our present-day Library) was opened. In its physical structure, the building embodied the global reach of Britain’s colonial power at its height. The huge 16.5m long pine beams that hold up the roof, and on which the original winching machinery was installed, were shipped to Lincoln all the way from Canada. The warehouse itself served as a focal point for an increasingly globalised trade: a building in which the goods of empire were organised, sorted and sent on to destinations across Britain and around a globe that had been reshaped by colonialism. Today, the Warehouse – and its new Library occupant – plays a similar role in collating, organising and sharing forms of knowledge. The history of this building should inspire us to ask: what sorts of knowledge “goods” are organised and catalogued here? Who is able to access and benefit from this warehouse of knowledge? Our hope is that, just as the physical form of the Warehouse has been disrupted and given new purpose by its architectural transformation into the University Library, we can transform and decolonise our collecting, cataloguing, knowledge sharing and librarianship to better reflect a post-imperial, plural United Kingdom – and to better serve the global community of scholarship, research, pedagogy and practice of which we are a part”.

Dr Simon Obendorf

Senior Lecturer

School of Social and Political Sciences

College of Social Science

Decolonising is a term that you may have heard a lot about recently as it has gained traction in Higher Education in recent years. At Lincoln, several key groups have been set up to discuss what it means to us as an institution and how we are going to move forward to address the issues.

Decolonisation of HE originated as a movement 20 years ago to ensure that the knowledge and practices of indigenous people were represented in the HE curricula of post-colonial countries.

“More recently the ‘decolonising the curriculum’ agenda was reignited in South Africa in 2015 with the “Rhodes Must Fall” movement, where students demanded the removal of the statue to the colonialist, Cecil Rhodes, and for indigenous knowledge to be placed on an equal footing in the curriculum with that from the global north. This agenda has gained momentum in the UK, led by the National Union of Students ‘Why is my curriculum white?’ campaign which suggests that while the Arts and Humanities disciplines have the most work to do regarding decolonisation, all subjects have opportunities to reconsider teaching matter”. Dr Neil Williams, Kingston University

So, the opposite of a decolonised curriculum is a colonial curriculum. A colonial curriculum is:

- Unrepresentative because it selects particular teachings and excludes others

- Inaccessible because it consequently prevents recipients of the teaching from identifying with the narrative (but appealing to the historically favoured demographic)

- Privileged because it continues to ensure that this select group of people is the dominant narrative

As a University, we have committed to recognise and uphold the five principles of our One Community Values: equality, understanding, listening, kindness, acceptance. The present project of decolonising our curriculum and pedagogy flows from and embeds this commitment. This means that we should critically question the ways our scholarship, teaching and practice have been shaped and look at ways that the Library is able to contribute.Historically, the voices of Black, Indigenous and other non-White people have been silenced, misrepresented or suppressed. This is the key focus where we can engage with decolonisation across the University. We must also remember to situate our thoughts and actions around this with the intersecting aspects of gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, dis/ability and/or religion.

Everyone in the University can play a part in thinking about these issues – thinking about the sources of knowledge that have been marginalised and drawing on a broader range of voices, ideas, approaches and intellectual perspectives.

The Library is an integral part of this way of thinking. It also goes way beyond adding a few extra texts to a reading list. It is also a different but linked agenda to the work around Equality, Diversity and Inclusion.

To decolonise, not just to diversify, recognises that knowledge is marked by power relations in which straight, white, hetero upper class men, still have disproportinate prominence.

From the Library, Hope Williard and Oonagh Monaghan are on the Decolonising steering and working groups. Hope and Claire Arrand are also on the Reimagining Lincolnshire group. Hope and Oonagh have attended various related conferences and events over the last couple of years and recently contributed to the University of Lincoln IMPact Journal which is a peer-reviewed, open access journal. The article ‘Critical reflections and collaborative approaches to the University of Lincoln’s decolonising projects: A library perspective‘ was included as part of a special issue on ‘Race matters: towards and Anti-praxis in higher education’ and was a reflection of the these events and how they have influenced planning and practice for the future in the Library at UoL.

Decoloniality at Lincoln Toolkit

The Library toolkit is designed for everyone in the University community to understand more about decolonisation work. https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/DecolonialityAtLincoln This currently sits under the ‘Learn’ menu of the Library Website but there are plans to highlight this more during the University year.

Each subject guide should have a section introducing the topic and have specific subject related links. https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/design/Decolonisation and the aim of this is to provide a student friendly introduction to what it means and how it relates to their experience of HE.

There is no simple ‘to do’ list or quick fix to decolonise the Library but we take our starting point from thinking critically about our current practices and policies. Critical librarianship aims to put issues of social justice at the centre of everything we do.

- What are we doing as part of our equality and diversity practices?

- Do we represent the lived experiences of the people who work and study in the University and Library?

- Do we collaborate with our users and enable exploration of the collections in new ways? What does our collection consist of?

- How do we decide what is in the collection?How can we amplify marginalised voices? How can we challenge the status quo?

If we take action in our policies and interpret and disseminate what is in our collections, more students and staff will be able to understand what decolonisation is and how the Library and it’s engagement with staff and students is instrumental in the wider processes underway in schools and colleges.

Watch this space for the next steps in the Library…..