A talk for Mercian Collaboration – reflections on the journey at Lincoln

Oonagh Monaghan (She/Her) , Academic Subject Librarian and Decolonising@Lincoln Library lead

I’m an Academic Subject Librarian at the University of Lincoln. I support the subjects of Fine Art, Design and Architecture and have worked at the University for over 20 years. Over the years I have supported various disciplines, however, over the last few years I realised I have always been an art librarian at heart! A few years back I attended the UK and Ireland Art Libraries Society (ARLIS) conference in and it was then that I began to think more deeply about critical librarianship, decolonising collections and creative innovations. During my talk today I will be acknowledging others who have been influential in my own development.

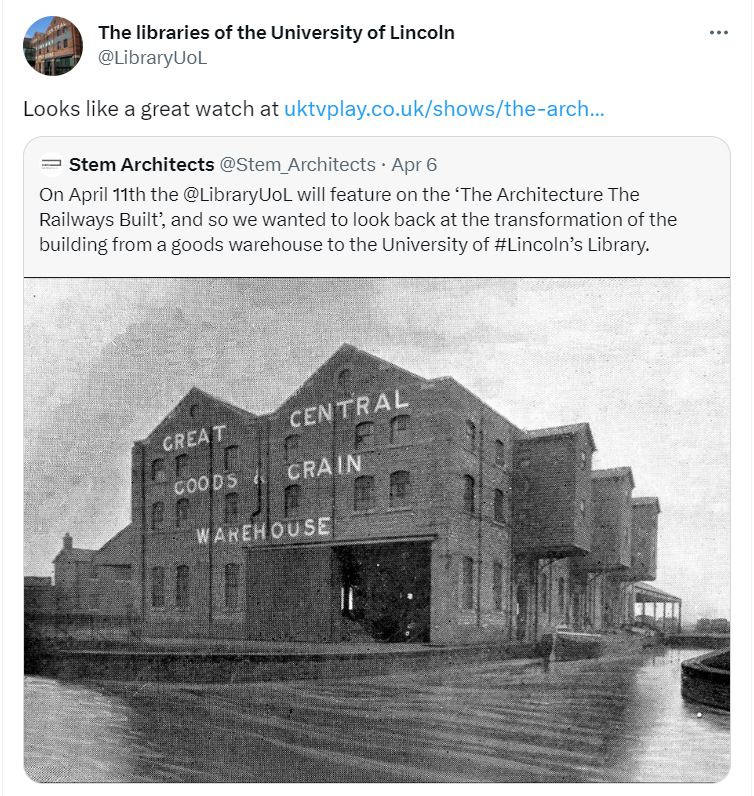

We have three libraries – one at Holbeach, one based in the Medical School in Lincoln and the main Library where I’m based. The Library is a converted railway warehouse and as you can see from this tweet, it recently featured in a documentary called ‘The architecture the railways built’ – you can also see here what the building looks like now.

I was interested in how we could relook at the history of the building itself, so I invited academic Dr Simon Obendorf to write a blog post about the building’s site, purpose and physical structure and how it provides us with many opportunities to reflect on Britain’s colonial past. Any links I refer to today will be made available so you can read more about this in Simon’s post on the Library blog.

There may be scope in the future for doing more about the colonial history of the building to highlight these aspects of this history.

One person who has been very inspirational to me is Marilyn Clarke, who is former Library director at Goldsmiths and now Librarian at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies. 2

“I as a library worker seek to transgress against the boundaries imposed by racism, classism and heteronormative structures in both knowledge dissemination and organisation, as well as institutional structures” Marilyn Clarke, 2019

This quote by Marilyn encapsulates my starting point when thinking about decolonising activities. I’m very conscious of my own privilege as a white middle-class, cis, heterosexual, able-bodied person and the fact – that here we are today – three white librarians talking about decolonisation and libraries.

Recently Naomi Smith who is Assistant Library Manager at UCL ran a webinar entitled ‘Librarians for critical digital justice’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8h1AREn5t0 and talked about not skirting around issues with soft words like inclusion and diversity and instead using terms like white supremacy and institutional racism. I agree that we can get lost in bureaucratic tick boxing exercises in Higher Education. My starting point has always been from a critical librarianship position, and I don’t believe in neutrality within the library setting. Critical librarianship means for me that I’m always trying to think of my work from an intersectional and social justice perspective and also that I need to be on a continual process of learning from others.

The University of Lincoln has developed action plans within schools and colleges and has commitment from the senior management team to make decolonising a serious and long-term project. As part of this plan, professional services departments are included and the Library is central to both developing professional services understanding and also engaging with the academics and the curriculum. The initial and ongoing aims of the Library are to

- Reveal coloniality of existing collections

- Challenge coloniality

- Research decoloniality

- Embrace and extend decoloniality

So, what can we do in our libraries to dismantle what is already in place and rethink the knowledge distribution? There are no easy answers and we may now actually be starting to overuse the word ‘decolonise’ and inadvertently diluting the issues that are holding up the colonial structures.

Naomi said in her talk that many libraires are simply doing inclusion work and diversifying collections, and I agree that this can so easily happen. So, we really need to think deeply about what we can do to challenge this.

My talk is not offering any defined solutions to these issues but instead I will be talking about my journey with the ‘Decolonising@Lincoln’ project and developments in the University and within the library that I hope will start more conversations.

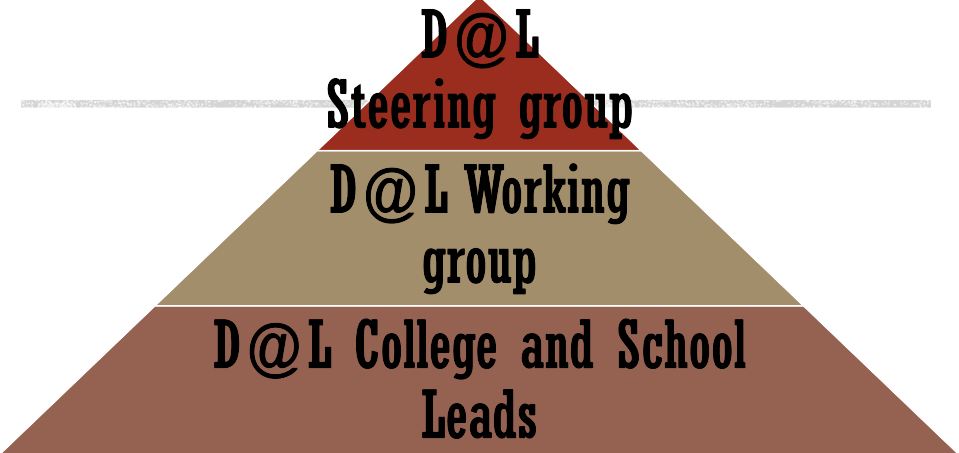

I got involved in a lead role as soon as the University created a project around decolonisation and have worked with my colleague, Dr Hope Williard who is also a College of Arts Librarian, as Library liaison on both the University Decolonising steering and working groups.

So the library is actually involved at every level since the onset of the project.

I think this is key.

For the Library to be central to all University discussions so that it then cannot be separated from discussions around the curriculum. As you can see from the chart, in addition to the steering committee and working group, there are also College and School leads and at this level, all the other Subject Librarians are required to work with their academics on decolonising projects.

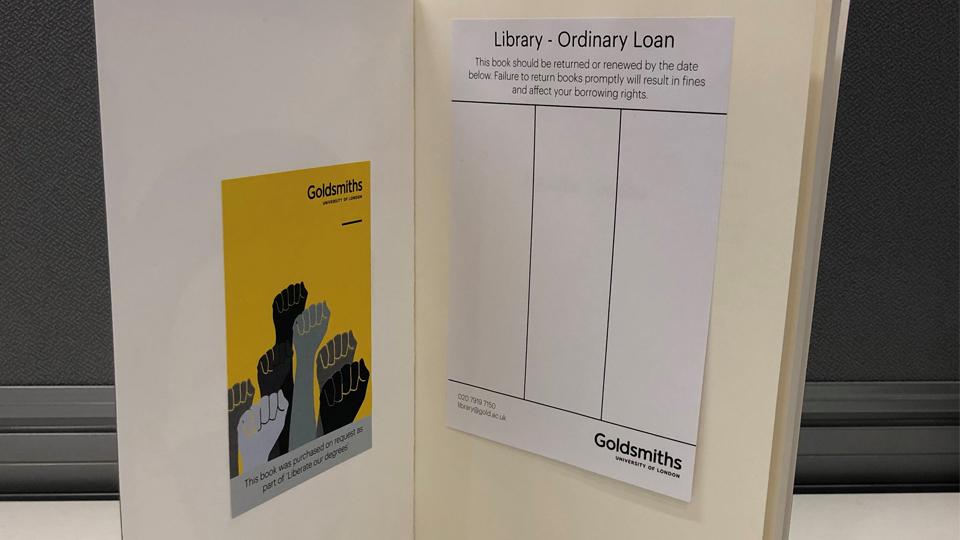

The first thing we did practically was draw together information from our own institution and from other University libraries and I have been particularly influenced by the work on the ‘Liberate our Library’ campaign at Goldsmiths https://www.gold.ac.uk/library/about/liberate-our-library/.

You will notice as well that we use the terms decolonisation and decoloniality.

There is a very good explainer of these terms and the differences on a University of Arts London (UAL) article ‘Decolonising the library: a theoretical exploration’ by Jess Crilly who also co-edited the book ‘Narrative Expansions with Regina Everitt – another recommended read. https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/123/190

As part of my initial research for the toolkit, I contacted Caroline Ball from the University of Derby as I had seen the great work she had already done. Caroline’s work helped me get started with the D@Lincoln tookit which is available on our Library website https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/DecolonialityAtLincoln.

As the toolkit was the first thing we did, I do think we need to look at this again very soon. It has been used as a focus for the University academics and professional services staff where there was nothing else visible.

Now that the University has moved forward and is developing their central Decolonising@Lincoln website, the library content can now be revised and improved.

I also want to get away from the idea that just by diversifying reading lists we can tick off decolonisation as being ‘done’. When we initially set up the toolkit on Libguides software, I had permission to use a great reading list audit tool from Manchester Metropolitan University, but I gradually became aware that this actually potentially hindered the conversation and facilitated the tick boxing approach rather than thinking more deeply about the curriculum development.

I have also now created a separate Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Guide with the emphasis being on diversifying the collection.

So often, there is confusion about the difference between the decolonising work and the EDI work. The new EDI guide will allow us to develop the Decolonising@Lincoln Library toolkit and move away from the focus of diversifying reading lists as the main outcome of library involvement.

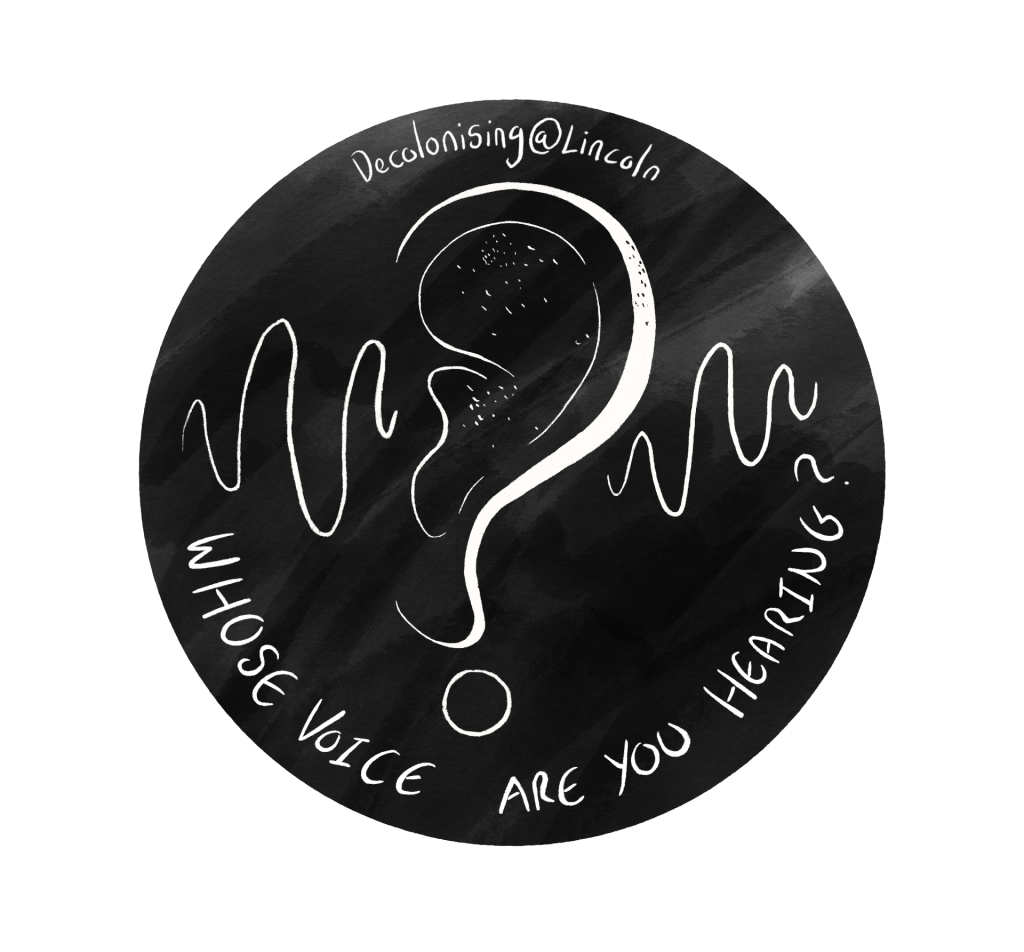

The bookplates in the Goldsmiths ‘Liberate our degrees’ initiative inspired me to think about a design for our own libraries and one that could be used on promotional material, campaigns, bookmarks and shelf-ends. I organised a project with the School of Design for the students to submit entries to a competition in 2022 and the judges included School of Design academics, decolonising steering group members and Marilyn Clarke who was then Director of the Library at Goldsmiths.

The competition was shared with all of the School of Design students via the Blackboard VLE noticeboards and via a publicity, using posters and social media. I also did an Adobe presentation https://express.adobe.com/video/tiVyWQG6CrNSI which I could share with students and help them understand the background to the decolonising initiatives. It was a massive effort on my part to try and get the students to feel confident to enter the competition alongside all the other work they had to do on assignments and dissertations, but by the competition deadline, we had six entries. This doesn’t seem like a lot, but I was really pleased with the thought processes that I could see within the designs. I could tell that the students had had conversations with academics had done their own research. The judging panel consisted of myself, School of Design academics, Decolonising@Lincoln steering group members and external judge Marilyn Clarke.

We eventually decided on a winner and had two runner-up prizes. I organised a prize-giving event and invited all the key stakeholders and the three students – this was covered by the Marketing team and featured on the University staff news, social media channels and on the Library blog.

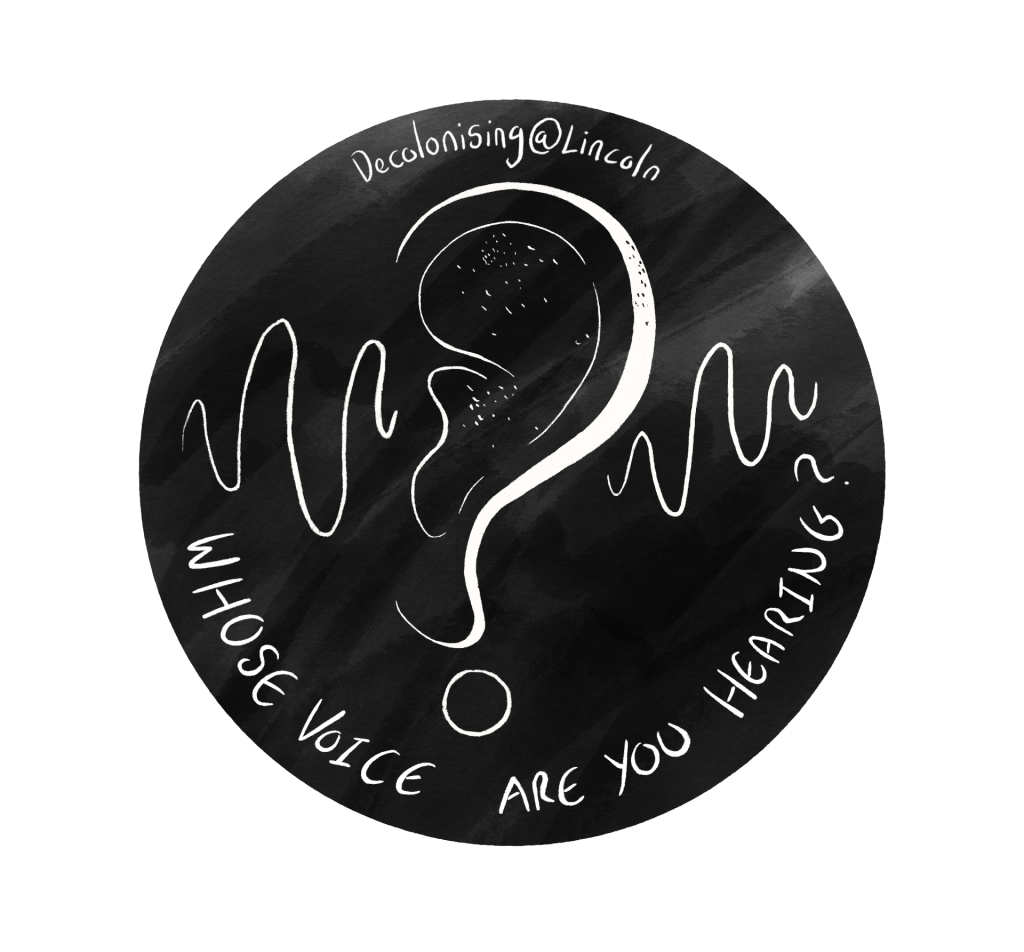

So here we have the winning design by Kes Whyte which we now have as a recognisable University of Lincoln image to use on materials and on the web. I have included the Instagram handle of the illustrator as they are now out in the real world for you to follow.

In addition to the winning image, one of the runner-up images was so good that we decided that we wanted to turn this into a mural in the Library. This has taken some time to negotiate and wasn’t without problems along the way, namely a pesky plug socket which you can now see is covered with a black socket plate (we also had to work with the student to redesign the whole image to suit the space). You can also follow Rhoda, who designed this mural, if you so wish, on Instagram. Both students are amazing artists.

One of the developments I’m most proud of is our new zine collection. I could do a whole presentation on the development of the zines!

If you want to find out more about zines, there is more about what they are, on the Library website https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/design/zines

I’m very proud that our Libraries and Learning Skills department now has a growing collection of zines and these are displayed on the ground floor the the main Library.

The collection includes zines donated by zinesters (which is the name for zine makers), zines bought by the Library via sites like Etsy and those made and donated by students in the University itself.

Zines have a long history of being used by marginalised and excluded people and communities due to their DIY and self-publishing format. The aim is to provide a medium that diversifies our collections further and challenges white-centred practices which impact our collections, users and services.

I’m always keen to take an intersectional approach and develop a zine collection which I hope will begin to help us think about the voices so often not heard.

In addition to the new collection, I have developed connections with academics, students and external people who have a common shared interest in zines. We have held workshops and I’m working with academics on other initiatives as part of the EDI agenda. You can also see on this photograph that we have a vinyl sign version of the ‘Whose voice are you hearing’ design produced by a great College of Arts Technician colleague who I’ve also worked with on a zines workshop in the Library.

Reimagining Lincolnshire https://reimagininglincs.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/ is a public history project based at the University of Lincoln.

Co-investigators include heritage professionals, teachers and researchers from a wide range of organisations in the region, as well as staff and students at the UoL and Bishop Grosseteste University. The project seeks to uncover hidden and neglected stories from Lincolnshire, of those whose contributions to the county, country and internationally have largely been forgotten.

I have been lucky to work alongside the project on various initiatives, one of which was part of a Wikimedia UK funded connected heritage project. (https://wikimedia.org.uk/connected-heritage/ Connected Heritage projects are a collaboration between Wikimedia and heritage organisations in England and Wales.

In October 2022 we organised a Reimagining Lincolnshire: Black History Month Wikithon where participants were invited to learn Wikipedia basics and make some edits to highlight some of the stories and people with connections to Lincolnshire.

Editathons aim to address the underrepresentation of people from the Global South, women, people of colour, LGBTQ+ people and other marginalised groups in Wikipedia entries and among contributors.

We had some great fun editing on the day and in particular a new article was created on Mahomet Thomas Philips https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahomet_Thomas_Phillips who was a sculptor and stone carver. The event coincided with an exhibition in the Library produced by the Reimagining Lincolnshire team.

Embedding decolonising into other events/history months/displays

I’m conscious that an integral part of decolonising is that we think about it in everything we do as much as we can. So, I have tried to integrate it in the other activities across the Library.

An example of this was the display that we had this year for LGBTQ+ History Month and which included a Talis reading list with lots of recommendations including books on global issues of sexuality, gender and decoloniality.

I also invited a contributor to our Library blog. Again, D@L steering group member, Dr Simon Obendorf, wrote a blog post entitled ‘Inside and beyond the +’ https://library.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2023/02/23/inside-and-beyond-the/ and we were able to link to various recommended texts within the Library collection.

Moving forward we can continue to think about future projects, widening involvement and all-team engagement. Communication and sharing knowledge is so important. The plan is to:

Continue to work on individual projects and events

- Next, we will be organising a whole Library team meeting where academics of the D@L steering committee introduce decolonising concepts and invite discussion

- We need to move the Academic Subject Librarians project forward – this involves collating information about existing curriculum initiatives which are already taking place in different disciplines and help us share good practice and ways of working together with the academic curriculum.

- We will be developing the information on our various different subject guides (on libguides) and working with the D@L champions within the schools to improve the subject discipline specific information.

- The Subject Librarians will also be working on identifying sections/books within the print collection which are either

- Problematic in content due to coloniality or

- Identify those sections/books which highlight marginalised or underpresented voices

- The aim of this is to utilise the School of Design/Library competition winning design which will be used on shelf-end and bookmarks with explanations. This will include highlighting the systemic bias of the Dewey Decimal system.

- I hope to invite speakers to an away day in the future and have a themed day on decolonising and EDI issues including the difference between them.

- And colleagues have started working on embedding these themes into our Information literacy and critical thinking aspects of the skills workshops. Goldsmiths also do something already around this with their ‘resistance researching workshops’ which are designed to help students think more critically from a social justice perspective.

- And finally, there is also an extra zine project I am working on which still needs to take shape. I successfully secured funding for a Reimagining Lincolnshire zine with the aim to amplify hidden voices from Lincolnshire’s past, but reflect on these alongside the lives of people living in Lincolnshire today. The zine will also include reflections and responses from students and staff at the University of Lincoln and people outside of the University – these could be creative responses or reflections on the past stories – or how the colonial past has impacted their own lives today or their experiences of Lincolnshire. This is ongoing but I will get it done! The problem is I have too many ideas and not enough time!

To conclude, I referred to Naomi’s talk earlier and in particular she spoke about the fact that Higher Education is ignoring the impact around the technology we use with – assumptions made from western perspectives and our over reliance on the internet which means – we are largely ignoring the knowledge from marginalised communities. One example of this is the oral word.

When we are thinking about decolonising we need to take into account different forms of knowledge from different people and not just prioritise Western forms of knowledge. I would recommend listening to Naomi’s talk on this issue in relation to our reliance on technology and commercialisation of Higher Education.

I think the technology and the commercial aspects of the University are so embedded in everything we do, that this prohibits us from really moving forward with decolonising work. My starting point at Lincoln has been around trying to get involved in conversations and bringing that knowledge and those questions back to the Library and then trying to make some creative and practical changes to help with the conversations. I cannot claim that it would even be possible to decolonise the University of Lincoln Library in my lifetime or at all. But what I can do, is raise awareness, encourage discussion, involve students and staff in thinking about the issues and be creative about working with the collections we have.

Resources and Links

Library blog post – Decolonisation, the Library and reflecting on the building and it’s colonial past https://library.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2023/03/28/decolonisation-the-library-and-reflecting-on-the-building-and-its-colonial-past/

Sconul information on Marilyn Clarke https://www.sconul.ac.uk/page/marilyn-clarke

Naomi Smith, Assistant Library Manager at UCL ‘Librarians for critical digital justice’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8h1AREn5t0

‘Liberate our Library’ campaign at Goldsmiths https://www.gold.ac.uk/library/about/liberate-our-library/

University of Arts, London article https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/123/190

University of Derby guide https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/decolonisation

Library and School of Design competition Adobe presentation https://express.adobe.com/video/tiVyWQG6CrNSI

Library and Learning Skills Blog – https://library.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/

Decolonising@Lincoln Library toolkit – https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/DecolonialityAtLincoln

Example Subject guide decolonising introduction for students – https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/ArchitectureAndTheBuiltEnvironment/DecolonisingArchitecture

Wikimedia Connected Heritage projects https://wikimedia.org.uk/connected-heritage/

Wikimedia Connected Heritage project with Reimagining Lincolnshire https://wikimedia.org.uk/2022/04/connected-heritage-partnerships/

Wikipedia Entry – Mahomet Thomas Philips https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahomet_Thomas_Phillips

LGBTQ+ History month reading lists including Global issues of sexuality, gender and decoloniality

https://rl.talis.com/3/lincoln/lists/9F6592A2-EAE4-E94E-2023-C1C7204B02A9.html

Zine collection information https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/design/zines