March is women’s history month and the library blog is celebrating by featuring posts from authors around the university about the lives and writings of women. Our second post in our series is by Rebecca Norman, a third year student on the BA History course. She explains the topic of her dissertation and how it helps us understand the lives of lower and middle class British women. Thank you for writing for us, Rebecca! This post has been guest edited by School of History and Heritage administrator, Emily Hanson. We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

When my grandpa found out I was writing my undergraduate dissertation on Denise Robins’ popular romance fiction, he commented that:

‘You don’t need to be paying to read that rubbish at University, your grandma has plenty on her kindle!’

Somehow, in his initial pride that his granddaughter was studying a ‘proper’ subject like History at university, he had not envisioned me carrying out a research project on what is widely regarded as ‘trashy’ fiction; but I’m about to finish off 10,000 words on the gender identities constructed and communicated in popular romance novels of the 1930s.

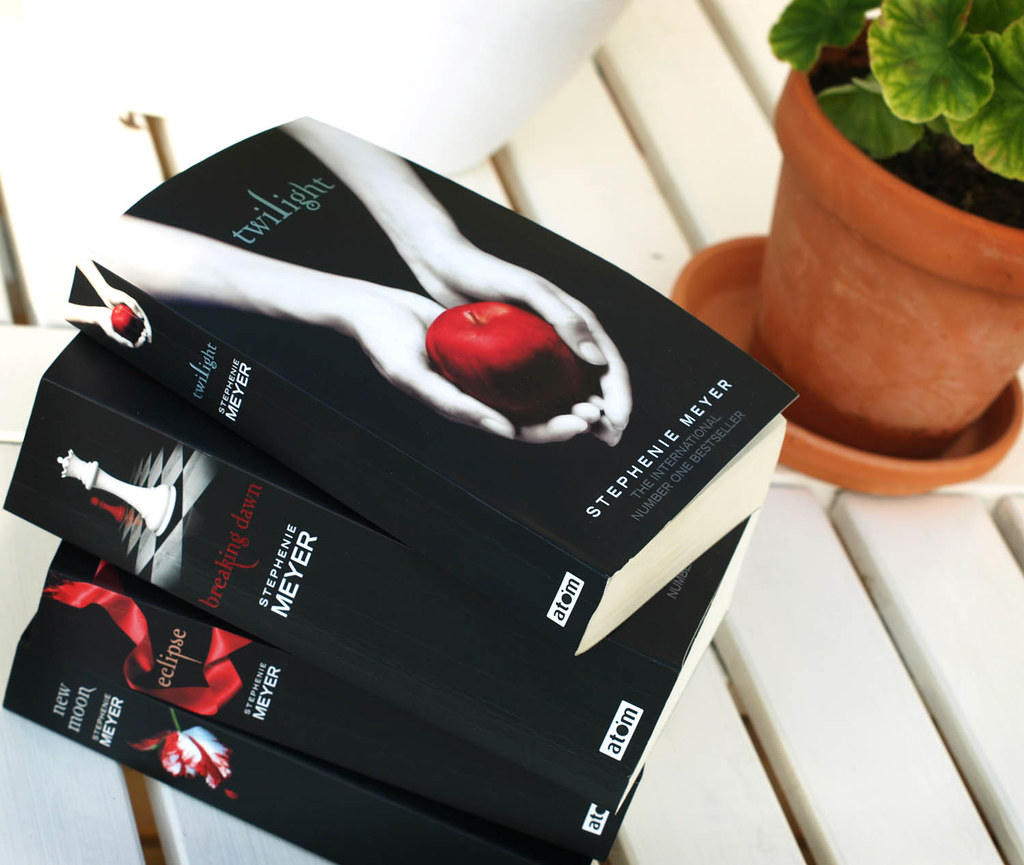

My interest in the significance of popular romance novels for women’s history was sparked by a debate in the second year module History and Literature (which I would highly recommend to anyone who’s interested!) where I found myself coming to the defence of low-brow fiction including Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight. My argument was that such popular fiction permeated deep into society. However much they professed to dislike the franchise, you would be hard pressed to find someone who has never heard of Twilight, or doesn’t have a vague idea that it’s a romance involving vampires. Its impact on collective consciousness in 2005 was therefore much greater than John Banville’s The Sea, which arguably (having won the Man Booker Prize for fiction) was a literary work of superior quality published in that same year.

“I love these books!” by missteee is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

From a historical viewpoint it makes perfect sense that engaging with the most popular narratives of a particular period could help us to understand what people at the time valued. Readers of popular romance in the 1930s were overwhelmingly lower and middle-class women, and therefore using the novels as primary sources offers some insight into the lived experiences of women who were less likely to keep extensive diaries, which was more common amongst upper-class women. Romance novels are of particular interest from a women’s history viewpoint as they were written almost exclusively by female authors, and so the ideas within them are produced by women for women; reflecting women’s concerns. One of the chapters in my dissertation considers the extent to which (male) publishers influenced ideas that female writers put into their novels: I argued that it wouldn’t have made commercial sense for them to do so, because women would buy (or borrow from commercial lending libraries, common in this period) books which spoke to their experience.

“Romance” by Stewf is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Romance” by Stewf is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Unfortunately, there has been limited interaction between historians and popular romance novels to date. Anybody interested in reading more about the topic should look at the work of Laura King, who has examined masculinity in mid-twentieth century romance, as well as Joseph McAleer who has researched the publishing of popular romance, and Lincoln’s own Christine Grandy who has investigated the consumption of interwar popular narratives (unfortunately not romantic ones!). Beyond this, it’s important to take an interdisciplinary approach; where other academic fields including literature and sociology have been engaging with popular romance novels much longer than historians. The Journal of Popular Romance Studies is a really good starting point for this.

My dissertation analyses the forms of gender which were constructed and communicated in a small sample of popular romance novels written by Denise Robins in the 1930s, but this area has so much more scope for further research across the 20th century. It could be really interesting to compare British popular romance with novels published in America in the same period for example, or to compare constructions of gender across novels and film.