March is women’s history month and the library blog is celebrating by featuring guest posts from authors around the university about the lives and writings of women. Our first post in our series is by Emma Fox, a third year student on the BA History course. She explains the topic of her dissertation and offers advice to students beginning to think about theirs. Thank you for writing for us, Emma! We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

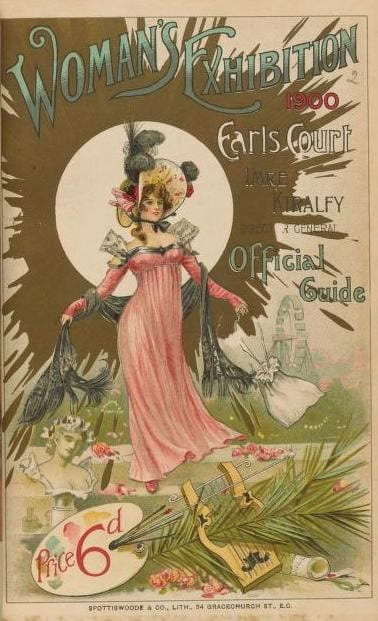

For my dissertation, I have been writing about the Woman’s Exhibition held in 1900 at Earl’s Court. This was one of many commercial exhibitions held by London Exhibitions Ltd under Imre Kiralfy who was known in both Britain and the USA for his spectacles and shows. My dissertation explores the exhibition’s representations of women and if and how these appealed to the public.

The exhibition appears to have been very well-received, which I have determined through the press response. Most articles highlighted the main attraction, the ‘Women of All Nations’, which showcased women and their ‘work’ (usually handicrafts) from 24 nations. The domestic focus of the exhibition reflected traditional views on women’s work but also, in emphasising the importance of the domestic space, reflected feminist thought of the time. Many feminists at the turn of the twentieth century, took no issue with the notion that women’s work was domestic work. They sought to build on this traditional view but change attitudes towards it, emphasising domestic work as respectable, distinct from and as important as men’s work.

Imperial exhibitions was topic of a seminar in one of my second-year modules, ‘Scrambling for Africa’. In particular, I came across the Woman’s Exhibition in a piece of set reading (Chapter 4 of John MacKenzie’s Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880-1960). It was mentioned only briefly but I decided to follow it up. To anyone who is choosing their dissertation topic and is slightly overwhelmed at all the directions they could go in, I would definitely recommend returning to any seminar topics you have found interesting and follow up the further readings recommended by your tutor. I have used mainly guidebooks from the exhibition and newspaper reporting on the event as my primary sources. I found all of the guidebooks on the site www.archive.org and have used the databases ‘19th Century UK Periodicals’, ‘British Library Newspapers’, ‘Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004’ and ‘The Times Digital Archive’ to find all of my newspaper material.

Before starting my research, I had an interest in women’s and gender history but didn’t know a lot about it. Due to the imperial character of the Earl’s Court exhibitions, this was initially my main focus. Approaching women’s history from this angle revealed the extent to which British feminism was borne out of an imperial context. Scholarship about women’s imperial activism and travel writing was particularly useful for understanding this, for example Antoinette Burton’s ‘The White Woman’s Burden’ and Clare Midgley’s, ‘Bringing the Empire Home: Women Activists in Imperial Britain, 1790s-1930s’.

Ultimately, the Woman’s Exhibition was a commercial event and so the choice to dedicate an exhibition to women is fascinating as it seems it would have been a big risk. However, it was well-received in the press and it has been incredibly interesting to explore the ways that Kiralfy mitigated the risk through appealing to popular imperialism, fun-fair style attractions and sticking to portrayals of women that emphasised their femininity.