Two questions. Would you wear a dead bird on your hat and are you a dedicated follower of fashion? Personally, my answer to both is a resounding no. Look closely at the image above, taken from an article written by Lisa Wade in 2017. At first sight it may be viewed as a thing of beauty until you look closer and see it is an actual bird, or an amalgamation of bird parts. I make no apologies for the shock tactics.

This blog is about hats, or more precisely the desire to stop the slaughter of birds, which were prized for their plumage and worn by women with complete disregard for the effect on the bird population. It is the story of a 30 year campaign fought between 1891 and 1921 against ‘murderous millinery’, its inspiration coming from reading Tessa Boase’s book ‘Etta Lemon: the woman who saved the birds’.

Below is an image of Lincoln High St. from a postcard franked in 1908, demonstrating the striking abundance of headgear.

ROBINSON/254 part

ROBINSON/254 part

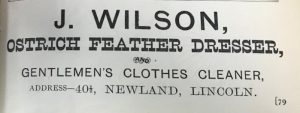

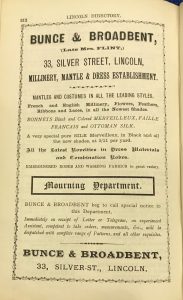

Milliners were located in every town alongside related businesses, such as the entry in 1885 for Mary Jane Harrison at 39 Baggholme Road Lincoln, listed as a milliner and feather dresser. This information was found in a Lincoln trade directory, as were the two adverts below.

Cook’s Lincoln trade directory 1895

Bunce & Broadbent advertised from 33 Silver St., a site of millinery since 1857 when it was run by Mrs Flint. Milliners were located around the city but concentrated on Silver Street, where there were up to 5 listed at any one time between 1857 and 1919, in either the Lincoln or Lincolnshire trade directories

Millinery businesses were the target for two different groups of women, Etta Lemon in Croydon and Emily Watson in Manchester. In 1889 Etta joined a branch of the Fur, Fin and Feather Club, appalled at the fashion of trimming hats with feathers and other avian decoration. This club joined with Emily Watson’s Society for the Protection of Birds and eventually became the RSPB. They decided to try and change public opinion, highlight this cruel trade and persuade women to solely use the available alternatives, fake flowers, lace and velvet, which were used when feathers were temporarily not in fashion.

These early women pioneers in animal welfare battled against the indifference of their sisters and the lucrative trade in imported plumage, with little success. As the use of feathers ebbed and flowed according to the dictates of fashion, thousands of birds were killed and imported into London. ‘At its peak, the trade was worth a staggering £20 million a year to Britain’ (1) around £204 million today. Bird populations were being systematically decimated, such was the demand. It was incredibly lucrative, snowy egret feathers being worth more than their weight in gold.

As business was booming the numbers working in the trade were huge, although it was not conducive to good heath, due to the use of mercury and dusty conditions often resulting in pulmonary tuberculosis. It was a precarious employment for those handling the feathers, as demand was sporadic and dependent on imports. The 1878 Factory Act reduced working hours to 56 per week, so lowly paid workers (usually women) were forced to continue at home in the evenings to make ends meet.

The numbers are mindboggling. On the 21st March 1888 over 12,000 dead hummingbirds plus numerous common and exotic birds such as birds of paradise and snowy egrets were sold in the plumage sale in Mincing Lane, London. In 1893 a shipment of 32,000 hummingbirds arrived, by which time 61 species worldwide were threatened with extinction (2).

CC0 1.0

CC0 1.0

SPB members were appalled at the continued use of the ‘osprey’, which used egret feathers only appearing during the mating season, resulting in the death of the parents and starvation of the nestlings. A mere ¼ of an ounce of feathers was produced by the death of each adult bird. Despite the best efforts of Etta Lemon and the SPB, their campaign fell on deaf ears. Hats were becoming larger and more ornate and in 1903 thousands of women were more concerned about suffrage than the fate of birds.

In the USA compassion exceeded Great Britain’s commercial concerns when the Plumage Act was passed in 1912. The rest of the world followed the USA’s example and only World War I put a temporary stop to the barbaric trade. Virginia Woolf wrote vividly about the slaughter and the first woman MP Nancy Astor added her weight when she entered parliament.

Thirty years after the start of the campaign the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Act was passed by parliament in 1921, following several previously unsuccessful attempts. It was not the end of the story but a step in the right direction, as it was a crime to import but not wear feathers.

Etta Lemon died in 1953 at the age of 92 and has been brought back to life by Tessa Boase’s research, alongside the forgotten women who campaigned so hard for their beloved birds.

With thanks to G. Jerwood, Sarah Lewis and Jack Kennedy.

References:

Boase, T. (2021) Etta Lemon: the woman who saved the birds. London: The Quarto Group. (1) px (2) p87

Hat images from Wade, Lisa (2017) The bird hat craze that sparked a bird preservation movement. Pacific Standard, 14 June. (https://psmag.com/social-justice/bird-hat-craze-sparked-preservation-movement-92745)

Trade directories exist for Lincoln from 1857-1975 and from 1842-1937 for the historic county of Lincolnshire (plus earlier editions of principal towns and large villages, not for the whole county) both in Lincoln Central Library and Lincolnshire Archives.