March is women’s history month and the library blog is celebrating by featuring posts about the lives and stories of women. This first post is by George Grant, library assistant at the Ross Library. Thank you for writing for us, George! We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

The role played by women in the history of medicine is a storied and contentious one. It is defined by the struggle against the formalised and male led medical field which often side-lined and overlooked the important role of women. From the Renaissance writers who tactfully avoided the works of classical female medical practitioners, to the role of the church in labelling medicine/wise women as witches, women have, at least in Western Europe, been forcefully kept out of the more formalised aspects of medicine. This began to change in the mid-nineteenth century, with the rise and growth of movements advocating for the improvement in women’s legal and education rights. These movements led many women to question their position in society and to push into fields that had previously been closed to them.[1] The following three short biographies show how, in this period, women were able to make significant headway into the professional medical field by gaining medical qualifications against significant opposition. They worked to inspire each other and train the next generation of female doctors. As it stands today, over half of GPs in the UK are women. This staggering change in less than 200 years was built on the foundations laid by these women and others like them[2]

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), the first woman to qualify as a doctor in the United States and the first woman to add her name to the British Medical Register. Born in Bristol, her family moved to the United States in 1832 when she was only eleven. Tragedy struck six years later when her father died, leaving Elizabeth in need of an income. She was initially opposed to the idea of working in medicine, stating that she ‘hated everything connected with the body’ and opting instead to teach. Seeing her friend dying of cancer and telling her she would have suffered less had she consulted a female doctor led Elizabeth to embark on a career as a physician. Due to her sex, she was denied access to formal training and told it would be impossible for her to become doctor. She continued to be denied acceptance into a medical school, approaching over fourteen schools before finally gaining admittance to Geneva Medical College in 1847.

Following her training, Elizabeth found work in London at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, befriending Florence Nightingale, amongst others, during this period. She ultimately decided to move back to the United States and establish her own practice in New York. Denied work at any hospitals, she was eventually able to raise the money to found the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857. Once again returning to the United Kingdom in 1858, she was permitted to enter her name on the British Medical Register due only to a clause that recognised doctors with foreign degrees. This clause was subsequently removed to prevent other women using it to gain their registration. During her life she had been reluctant to support women’s rights movements, however, her latter years were spent teaching the next generation of female physicians at the London School of Medicine for Women. She was and remains a complex and contradictory figure, yet one who undoubtedly paved the way for the next generation of female doctors.[3]

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917), the second woman to gain a place on the on the British Medical Register and the first to be admitted to the British Medical Association. Inspired to study medicine after meeting Elizabeth Blackwell in 1859, her family were initially unsupportive of the decision, her father believing ‘the whole idea to be disgusting’. With no British medical schools willing to train women, she therefore gained experience as a nurse on a surgical ward in 1860. She continued to be blocked from entering a medical school for further training by male students and instead studied privately at the London Hospital. She received her licence in 1865, although after she qualified the Society of Apothecaries stopped granting licences to those who had trained privately to avoid other women following in her footsteps. She set up her first practice in 1865, establishing St. Mary’s Dispensary for Women and Children in the following year and then the New Hospital for Women in 1871. She received her MD in Paris in 1870 and was admitted to the British Medical Association in 1873. Elizabeth continued to support the education of women as physicians alongside others, such as Sophia Jex-Blake, teaching at the London School of Medicine for Women.[4]

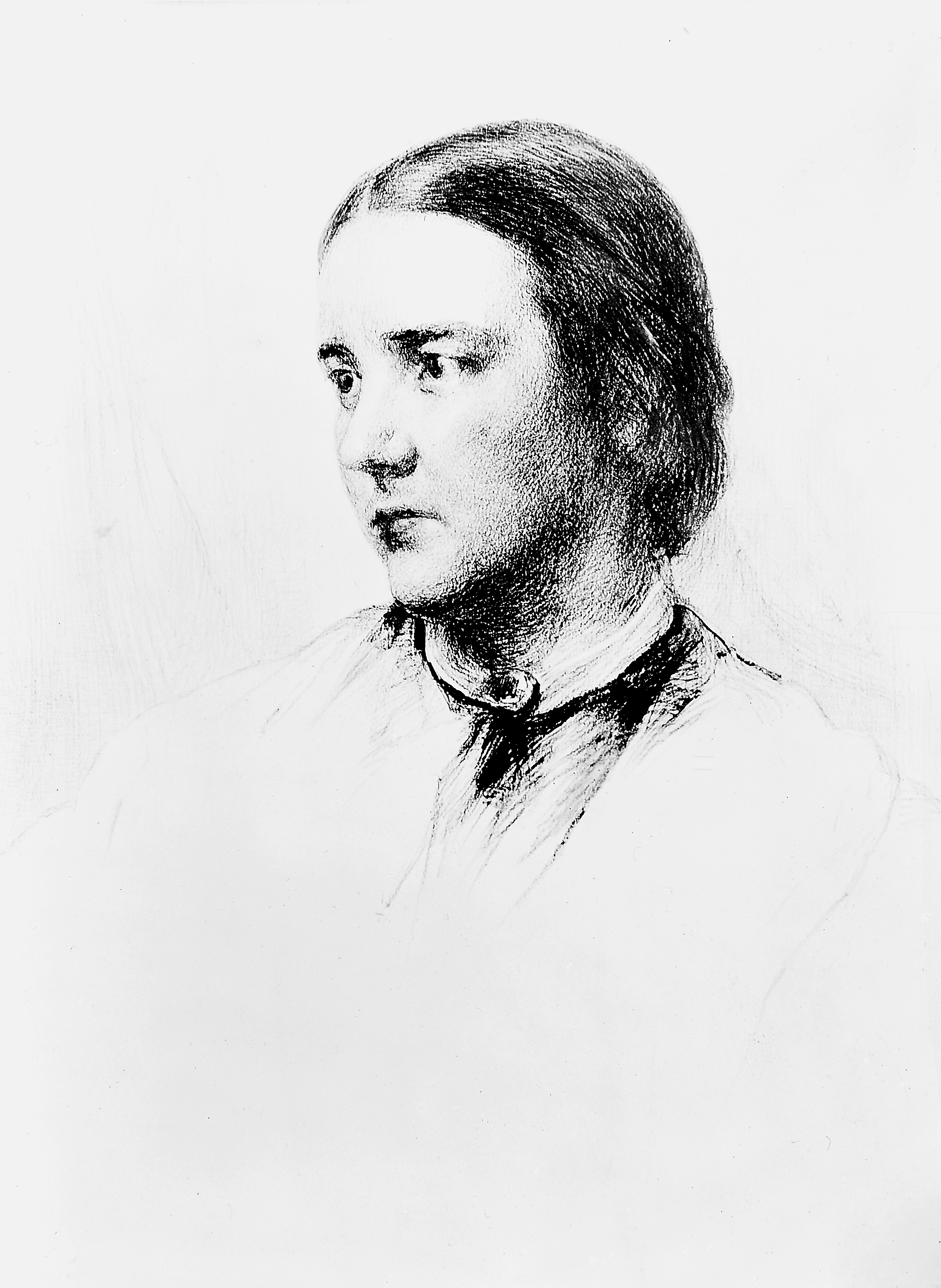

Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912) had a profound impact on the training of female physicians in the United Kingdom. Born in Hastings, she was a well-educated and highly capable child, described as ‘excessively clever’ by a fellow pupil at boarding school. Unhappy with the educational opportunities available to women, she attended Queen’s College London to train as a teacher. During an 1865 trip to the US, she ‘fell desperately in love with medicine’. Having been refused entry to Harvard she enrolled at the Women’s Medical College, New York, in 1868. Following her father’s death, she returned to the United Kingdom still intent on studying medicine. After being refused entry to the University of Edinburgh on the grounds that she was the only female applicant, she enlisted the help of four female friends who then applied together and, after passing the entry exam, were accepted. During her studies, she and the now six other female medical students at the university were accosted by a mob on the way to an anatomy exam, leading to the infamous Surgeon’s Hall Riot. The hostility they faced both from other students and faculty meant she was unable to graduate. She instead worked to establish the London School of Medicine for Women in 1874. Sophia developed a somewhat fractious relationship with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson who taught at the school and would eventually become dean in 1883. Jex-Blake finally received her medical degree from Berne University in 1877. She began practicing in Edinburgh and founded the Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children and the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women.[5]

These brief biographies outline the role that the three women played in helping the training of female physicians in the United Kingdom. It shows the importance of their grit, determination and desire to succeed, alongside their obvious intelligence. They do, however, only tell a small part of a much larger story. If the stories of these incredible women have inspired you to do some research and reading, remember that your subject librarian is here to help you locate and make the most of library resources. We encourage you to learn more about other pioneering women in the medical field and look forward to help you do so!

References and Further Reading

[1] Laura Jefferson, Karen Bloor and Alan Maynard, ‘Women in Medicine: Historical Perspectives and Recent Trends’, British Medical Bulletin 114 (2015), 5-15.

[2] Monica H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology (Oxford, 2008).

[3] Wendy Moore, ‘The Art of Medicine: Elizabeth Blackwell: Breaching the Barriers for Women in Medicine’, Lancet, 397:10275 (2021), 662-663.

[4] Laura Kelly, ‘The Art of Medicine: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: An Early Pioneer of Women’s Medicine’, Lancet 390:10113 (2017), 2620-2621.

[5] Elizabeth Ewan, The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, (Edinburgh, 2018), 218.