March is women’s history month and the library blog is celebrating by featuring posts from authors around the university about the lives and writings of women. The third post in our series is by Emily Hanson, administrator for the School of History and Heritage. Thank you for writing for us, Emily! We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

How young adult literature is clapping back to misogyny (and how this supports those most in need of advocacy)

I recently found myself writing a defense of young adult literature on my blog. I have always argued for the importance of high quality, relevant teen literature (or YA–Young Adult), not just for teens but for all of ages. At first glance, literature written from a teenage perspective offers the potential for representation that young people may not find elsewhere in traditionally published writing, alongside facilitating empathy for the modern teen experience. Beyond this, however, I argue that YA is a fantastic vehicle for exploring some of life’s most challenging experiences through the lens of those in a life phase where these experiences are new and deeply felt. In the context of women’s history, YA writing provides an excellent opportunity to empathetically ‘clap back’ to misogynistic issues faced by the young women of 2020.

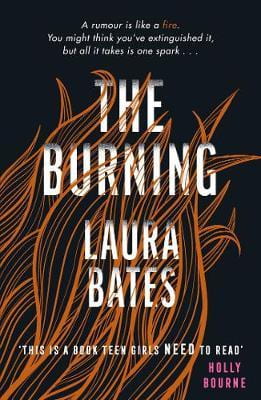

I found all of these things met and more in Laura Bates’ 2018 YA novel The Burning. You might know Laura Bates from her Everyday Sexism project, which calls out structural misogyny online, or her multitude of non-fiction works around the misogyny seen in modern culture. The Burning follows 16 year old Anna, living the deplorable truth that many young girls experience when they are made the object of sexual harassment and victim blaming. Bates places Anna’s story of a leaked nude photo alongside a 1650 witch hunt.

I was thrilled that an author passionate about combating produced a fiction work for teens (and adults who recognise the value of YA!). On reading this book in the space of 2 days I was utterly awed that this has to be one of the first books that has actually addressed teen victim blaming, modesty culture and sexual harassment from a teen perspective, for teens. I want to discuss how this book reflects the unsettlingly real world of victim blaming and harassment in the lives of teens, and how modesty culture worsens both.

A caveat

Before I go ahead, I want to roughly outline my perspective of the world. I’m a White, able bodied cisgender heterosexual woman brought up in a middle class privileged haze. I am very grateful for that privilege and the opportunities it has afforded me; and as a result of my privilege cannot speak for the multitude of intersections that worsen teen experiences of harassment: race, disability, economic status, sexuality and gender identity. All of these things complicate the issues I am about to discuss, and I want to recognise that my perspective and understanding of these issues are therefore simplified. I do however offer experience of being in, and then working in the education and youth sectors, and now at a university. I’ve witnessed and experienced these issues at every level and now act as women’s officer for my employer union. I have a very tiny amount of knowledge comparative with what the world can offer, but I think it’s my duty to share what I do have.

What is victim blaming/modesty culture?

Well when she was wearing something like that, what did she expect?

Girls these days. It’s like they have no self respect. Is there any wonder boys can’t concentrate?

What would your father say if he saw you in that?

She was asking for it. Leaving nothing to the imagination.

I really wish I could say that this is unfamiliar territory. That this kind of language isn’t spurted from the mouths of potentially well-meaning adults, parents, or news readers. This is victim blaming fuelled by modesty culture. Short skirt makes someone’s violence your fault. Long skirt and you’re protected. When a person is raped, attacked or harassed, our patriarchal culture would much sooner question why a woman would allow such crimes to be committed against her body and much sooner point the finger at her than accept an attacker’s responsibility for their own actions.

This phenomenon goes far deeper than ‘protecting’ young women against the apparently uncontrollable urges of teenage boys, a narrative which is complete and utter nonsense, painting intelligent young men as rabid animals and young women as damsels in distress (or deserving harlots, depending on their skirt length). It stems from a patriarchal culture which once burned women at the stake and now blames them for their rape rather than challenge established patriarchal authority.

How do we fix this?

Girls should know that their body is theirs to do with as they choose. The responses of others reflects on the issues held by those others, not them. To tell boys they do not need to repeat the errors before them, and that the lies of patriarchy fed to them as children (‘boys don’t cry, boys will be boys’) do not need to be blurted back out of younger mouths again, and again. Modesty culture might tell them different to this and victim blaming certainly will. But writers like Bates are changing the dialogue, and in their small way, handing back autonomy and worth to those that were never meant to bear the weight of patriarchy.

What I think Bates does beautifully is articulate, with the help of real teen girls who informed her writing, the issue of modesty culture vs peer pressure. I’ve been a teen girl and I’ve worked in secondary schools. Girls simply cannot win in the modesty war. Wear a dress beyond the knee, you’re boring. Above the knee, you’re promiscuous before you’ve even kissed a boy. I recall being at a party at 15 and in the space of half an hour being described as a prude for wearing tights and a slut for dancing with my friends. I’ve been chased by young boys on their bikes while on a run in a crop top, being told to ‘speed up love’, or ‘get them out for the lads’ (who were half my age). I’ve was honked at for wearing shorts at 14 walking to w friend’s house when it was hot. Called names for refusing to hug a stranger outside a bar when at university. What’s the common factor? NOT my dress choices. Patriarchy and an obsession with owning the female body is. I can look at this with confidence ten years later knowing the teen boys who said most of this at 15 are likely respectable men. But who was there at the time to tell me that my dress choice doesn’t dictate my worth, or that the urges of others was at issue, that my body shouldn’t be punished for existing? Who was there to tell the boys they were churning back out the misogynist lies they’d heard about the female body? I wish there had been a novel like The Burning.

To this end, we need young adult fiction to be recognised as a valuable contribution to literature. Universities and their libraries can contribute to this directly by having texts such as The Burning in their collections and reading lists, promoting these alongside their perhaps more established relevant canon. The Burning, for example, compares well with Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic, The Scarlett Letter; and opens up opportunities for literature students to recognize where their own experiences can relate to those depicted in classical works. Having these texts suggested alongside more frequently seen counterparts recognises their potential to contribute to established narratives on social justice. They are not simply a helpful addition but a vital contribution to ensure literary dialogue recognises not simply the issues of the past but what we as a society face in present day.

Final thoughts

We need to follow the model of people like Bates in recognising that victims are not responsible for their experiences of sexual harassment. The only thing victim blaming serves is preventing sexual harassment from being reported and letting perpetrators go free. We need to teach our teens the importance of consent and mutual respect free from judgement. We need to challenge when we hear victim blaming rhetoric. If we don’t, we’re throwing our girls on the bonfire and blaming them for not fighting the flames hard enough.