Dr Zakkiya Khan (they/them)

School of Architecture and the Built Environment

This post is the result of a talk I did for the School of Architecture and the Built Environment as an effort to process my own growing awareness of decolonising education. I wanted to share this process as a reflection and hope that somewhere something may resonate with readers.

This process began for me with awareness.

I started to unravel question my own experiences as a student and then new academic. I was aware I was different; people treated me differently, they expected different things from me, and I myself felt different from them. Yes, this difference may have been visible, but it was deeper than that. It was also about the society I was in and the one I’m in now.

This difference was not always received in a neutral way. I realised there were some things that needed reflection, some things that needed awareness. I reflected on all the experiences I have had both as a student and as an academic and I see ways that things could improve.

To do that, I wanted to use my position as an academic to reflect and learn to make educational spaces more inclusive. This is where I began becoming involved in institutional culture and curriculum transformation and decolonisation spaces.

- I first presented my talk on this topic in 2018 as an invited perspective to the University of Pretoria’s Anti-Discrimination Week.

- I represented the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment, and Information Technology Faculty’s (college) EBIT Curriculum Transformation Committee.

- I would like to bring awareness of the marginally empowered experiences University colleagues and students may face in the academic context.

Throughout my experience in the transformation space, I realised that the more awareness I was gaining, the more reflective I could be on the inclusivity of my practice and the educational context. Although there were limitations to what was within my control, I took an active role in pursuing knowledge in this area, attending conferences and reading books, participating in committees and engaging in projects that assisted to transform both institutional culture and the curriculum.

I noticed that the academic community, whether this was local/ global, within my field or outside of it, hold varying levels of awareness regarding equality, diversity, and inclusion. For the engineering faculty I was part of, vocabulary like ‘canon, critical pedagogy, hidden curriculum, etc.’ became difficult to access within the practicality of numbers and figures. I gained an understanding that the scope for decolonisation was broad, it had to be applied for a discipline/field, and it was applicable by the individual.

I think that by bringing various perspectives to the foreground we can all benefit by reflecting on our own positions in relation to our University community and the mindsets, we may hold that influence how we teach and what we teach. This is so that we can continually strive to be more inclusive in our practices.

This post is deliberately reflective. It’s important to note that I am not an expert in this subject. It has just been of personal career interest, and I am sharing my own views in the hope that could spark some interest and reflection in others.

Transformation is an ongoing journey. It is a process that never stops. It is about a continual interrogation of ourselves, our positions as educators. We are gatekeepers of knowledge and with this we have a sense of responsibility to the process of knowledge production. This includes the way we produce knowledge, not only in research but also teaching and learning and our subsequent influence on the built environment professions through our graduates.

Why is this awareness and reflection important?

- The University of Lincoln’s ‘One Community’ values champion inclusivity and diversity.

- There is a need to expand our understanding of diversity beyond ‘face-value’.

- The ‘Student as producer’ philosophy exists as a flagship opportunity to redefine the processes & products of ‘knowledge production’ when we value and appreciate diversity of our colleagues and students.

- The power to transform knowledge production (through education, research, and the profession) sits with each and every one of us.

I first came across the term intersectionality in around 2015 or so when the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement erupted. Apart from this growing global awareness of the marginal experiences of black communities, a concurrent activist movement sparked in South Africa through ‘Fees Must Fall’ – a protest surrounding the access to higher education and the limitation of this access to people with means. Pre-covid, this protest was the first significant shut-down inducing activity since Apartheid boycotts in South African universities. It raised questions and awareness surrounding equality and justice in the educational context. Questions on initiatives such as Black Economic Empowerment, retribution through education, what if the cure for cancer was in the mind of someone who could not afford an education? And pedagogy of the oppressed, all rang very high notes in my privileged life. I never had to worry about food on the table, transport to university, having running water, or access to education, yet this was the reality for most South Africans, and it made me question my role as an educator in providing just and equal education. This and my concurrently developing awareness of my own queerness, reconciling this with being Muslim, being a mother, trying to understand how I can feel so different and privileged, and conflicted – I grappled for answers in books and found intersectional feminism as a place that provided some answers.

The term, “intersectionality” was coined by critical race theorist, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989 in her essay “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Colour”.

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework derived from the social sciences. It acknowledges the increasing levels of marginalisation which may be experienced by individuals based on compounding factors of one’s identity.

This is reinforced by institutional structures as socially ingrained systems. These systems are not visible but reinforce power dynamics reinforced by patriarchal values that situate identity within a hierarchy and within boxes / associations.

Intersectionality acknowledges that compounding characteristics that individuals possess may contribute to consequent experiences of marginalisation and empowerment that they may face at any given time.

The awareness of movements such as BLM, reinforce the discrepant violence and disregard that black people face due to social prejudice.

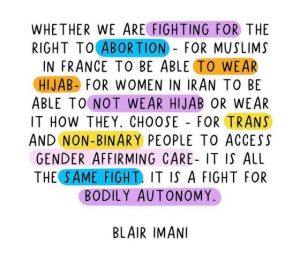

These systems benefit no one as they limit definitions of identity and serve particular frames and boxes. Phrases such as ‘boys don’t cry’ and ‘a woman’s place is in the kitchen’ reinforce some of these ideals. Intersectionality sees that additional burdens exist when certain facets of identity overlap and create difficulties in marginal experiences that can be alienating for the people involved, for example ‘being gay is haram’.

And what about the educational context? This is not about fitting a compartment or box. I realised according to an intersectional perspective, you can intersect, you can be many, and that as an educator, the ability to cross between understanding one position to another and reconcile these have been so valuable for my students, it can create belonging and synergy in the unexpected. It is a position of radical acceptance. It makes space for diversity and range not only across a group but within an individual and within the self.

These intersecting identities, although a source of overlap and empowerment, also highlight the nuanced struggles that marginal groups may face due to compounding factors.

Certain stigmas, prejudice, and conflicts between various social contexts can alienate whole communities. The black trans community are targeted and are particularly vulnerable to violent crimes.

This layered marginalisation presents unique systemised oppressive experiences that make access to social acceptance for this group extremely difficult.

This all occurs because of narratives on normativity. What is deemed normal? What is centred? What is considered legitimate? And where is this legitimacy rooted?

What are our positions in relation to these narratives? Can we ask ourselves – who’s voice are we listening to? Are we in a position of social privilege? Does society determine / favour our perspective as the norm?

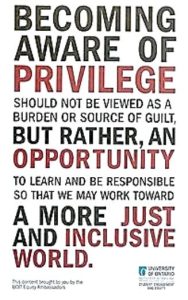

One of posters about racial privilege at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology have sparked controversy. The posters have been removed pending a ‘discussion event’ organized by the UOIT Office of Student Life. (Photo from UOIT Facebook)

For me, most certainly during ‘fees must fall’, this became a clue to disrupt my perspectives and practices. My socio-economic status as a middle class educated person meant that I never had to worry about not being able to access education. Just because it was not a problem I faced, it did not mean it didn’t exist, and it certainly did not mean I should not care about it.

It made me question: How can I relate my own positions within this social normative context to disrupt these patterns and champion a more inclusive institutional culture?

I began to learn that depending on a system of normative contexts, we may experience privilege and marginalisation concurrently and discrepantly across society. Some social systems will have no frame of reference for some aspects of social inequality and in others, this may be so severe, they result in exclusion and marginalisation of an individual from a community – whether this is religious / educational / institutional / communal / otherwise.

For example, being ‘out’ in Islamic spaces may result in me being excluded from my Muslim community, and likely my own family units in South Africa.

In the educational context, our individual positions hold certain norms and ideals that we bring to the university context. These in turn may place in institutional positions of marginalisation or privilege – a nuanced but relevant experience in an international and very diverse University community.

Although we would all like to see a transformed society, this is an ongoing process in a very long process that stems from colonialism and ongoing structural inequality.

One of posters about racial privilege at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology have sparked controversy. The posters have been removed pending a ‘discussion event’ organized by the UOIT Office of Student Life. (Photo from UOIT Facebook)

Structural inequality is cyclic.

This is because:

- Social advancement is not accessible to marginalised groups (as structural systems favour the progress of ‘normative’ identities) and

- There is a lack of representation and critical mass of marginal groups in positions of influence (that can open doors and show that it is possible).

It is up to us to break the cycle.

Depending on context, interrelated factors of marginalisation and privilege can occur concurrently

These filter into everyday life in the form of barriers or admittance in:

Education, knowledge, job opportunities, justice systems, career progress, spaces, resources, legal systems, and more.

Depending on our social positioning, we may find that we are marginalised / privileged / both in some instances.

Reflecting on my own identity, and trying to be aware of my privilege can give me some clues as to the objectives I need to occupy in light of above.

- My privilege shows me spaces I need to educate myself about and where I need to act in active allyship with marginalised communities.

- The other areas show where I will need to champion and uplift my own communities with the scope I have as an under-represented member of a community within positions of influence. Occupying concurrent positions does not mean I know everything or speak for all these groups, all it means is that I am a version of representation that can help others.

Positionality and privilege

- Positionality is the way in which we are positioned based on society’s relationship with our identity.

- Privilege exists where these positions afford us advantages and norms with no barriers or obstacles based on our identity.

- Privilege can result in blind spots – taken for granted norms and ideals mean that we may overlook certain behaviours, actions, and approaches that could be causing harm.

- This means that our taken for granted cultural capital may mean something different(or even negative) to communities outside the ‘dominant group’

- We can take action through self-reflection, accountability and using our privilege to challenge our own normative thought patterns and those of the people and systems around us.

As an example, the red cross red crescent.

“The red cross emblem has no intentional religious meaning. However, in the nineteenth century, the symbol reminded soldiers from the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey) of the crusaders of the Middle Ages.

So, since 1876, some countries have used a red crescent emblem in the same way as other countries used the red cross emblem.

On the basis of its use over several decades, the red crescent emblem was formally recognised in the updated Geneva Convention of 1929.

An additional distinctive emblem – the red crystal – was created in 2005 to increase protection in situations where the existing emblems may not be respected. It also helped to promote the universality of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. So, you may see members of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in other countries using the red cross, red crescent or red crystal.”

The red cross movement changed its name to red cross / red crescent, adding a red crescent to its symbolism as the cross was viewed to be too closely associated with Christianity by Islamic nations. These symbols show both a willingness to enhance inclusivity of a humanitatian organisation but also the oversight of symbolic meaning beyond Christo-centric global society.

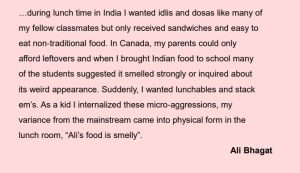

This testimonial by Ali Bhagat demonstrates a microaggression – a way of marginalising and othering a person based on their ‘unusual’ food. It may seem alternative to the everyday food of Europeans, but it is a staple in the sub-continent. It brought stigma to familiarity and alienated Bhagat.

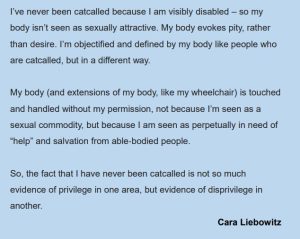

Ableism sees that disabled people are subjected to experiences that diminish their unique human characteristics through saviour-attitudes of able-bodied individuals seeking to aid them.

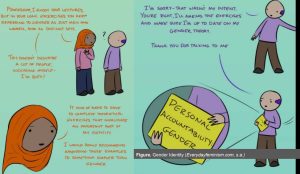

The image above talks about a student’s marginal experience in response to gendering. The student, who may be bigender or gender non-conforming has the confidence to raise this with their educator. As a person in authority, they take the conversation seriously and strive to use more gender inclusive approach. A damaging response would be to mis-gender them, or to question them, or to ridicule them.

As my religious identity continually reminded me of special measures and arrangements having to be made to accommodate me – from dietary requirements, to religious holiday accommodations, to prayer times, this life long special requests feel like an infringement on my freedom and even played a role in my access to higher education.

Had I slipped up in some way with my answer, that would have reduced the people of colour across an entire year in a programme to two people. This disproportionate to the demographic composition of the country.

Although the University of Lincoln has distributed resources and information pertaining to inclusion and transformation, its important to remain with a critical lens. No centre or unit is immune to the mishaps of exclusionary practices.

Here, cause-washing, unaccountability, and buzz-wording overtake the meaningful work of decolonisation and this occurs at the expense of marginal groups.

Positionality and marginalisation

- Positionality is the way in which we are positioned based on society’s relationship to our identity.

- Marginalisation exists where these positions do not align with societal norms and present barriers or obstacles based on our identity.

- We may not always see an experience as marginalising as society has preconditioned us to believe that norm = correct and that we need to assimilate to be acceptable within normative frameworks.

- We can take action by being the representation for these marginal groups,by setting an example as a role model, opening doors, and remaining true to our identities.

- This can be a lonely and pressuring experience as individuals cannot carry the weight of fully representing the views of a community or group.

My PhD was my goal but I also did it because I had no option. To be deemed acceptable, I had to do it. Not everyone had to live up to this expectation to access the same positions and opportunities I have had to, and this remains true for me and it will be true for these students who resemble me in cultural heritage.

As this new form of intersectionality has given me a platform of representation, I see my students and colleagues who struggle with access as my inspiration.

No one handed them a thing. With all kinds of barriers, this student and colleague have risen above it all.

My message in this post is to show the importance of reflection in developing my practices in teaching and learning. I discovered that pride in my own otherness gives others the space to know that they are safe enough to be themselves.

The Black Lives Matter pride flag symbolizes the way in which struggles are intersecting and the way in which communities can come together in joint pride to assist each other in allyship.

As with my pronouns badge representing my pronouns they/them, this pride symbol holds special meaning for me. It is about showing awareness that identity is not assumed, people are seen and valued and that being themselves in all facets is completely safe and welcome. That when I teach, Lincoln School of Architecture and the Built Environment is an inclusive and safe place of learning, where everyone’s identity is respected and treasured.

To read more and learn about how we can progress in decolonising teaching and learning, follow the link to the decolonising at Lincoln Library Toolkit https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/DecolonialityAtLincoln

References

American Program Bureau (2023) Kimberle Crenshaw. Newton, MA, USA: APB. Available from https://www.apbspeakers.com/media/2632/crenshaw_kim.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&quality=70&height=

775&rnd=131431182280000000 [accessed 31 October 2022].

Johnson, B. (2018) Racial ‘privilege’ campaigns at 2 Canadian schools spark controversy. Brandscovery. Available from https://brandscovery.com/world/content-2254535-racial-privilege-campaigns-2-canadian-schools-spark-controversy [accessed 31 October 2022].

Red Cross (2023) Protecting people in armed conflict: Find out more about the Geneva Conventions, the protective power of our emblem, and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Red Cross. Available from https://www.redcross.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/protecting-people-in-armed-conflict [accessed 31 October 2022].

Ollerenshaw, T. and Baggs, M. 2020. Black Trans Lives Matter protest: ‘Why we’re marching’. London: BBC. Available from

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-53192703 [accessed 31 October 2022].

Clarke, L. (2020) I’ve never been catcalled, and I don’t know how to feel about it: Walking the tightrope of disability, street harassment, and sexual desirability. Medium. Available from https://medium.com/conscious-life/ive-never-been-catcalled-and-i-don-t-know-how-to-feel-about-it-af6cecca6cdf [accessed 31 October 2022].