This is the fourth and final in series of four posts about using library collections for the study of black history, literature and culture, in Britain and abroad. We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

We hope you have had a wonderful, inspiring, and educational Black History Month! Our final post in this series will offer some suggestions for online databases and library resources for researching Black history in the county of Lincolnshire. This post will come in two parts: in the first part, I will discuss researching Black history in Lincolnshire. In the second part of the post, I will point you towards local collections, archives, and online projects which may help in your investigation of local Black history.

Researching Black History in Lincolnshire

Historically, Lincolnshire has had a smaller non-white population than other areas of the county. Publically available census data and statistics from the University of Lincoln Human Resources department provide a place to start. According to the 2011 census, 2.4% percent of the population of Lincolnshire identified as non-white, an increase from 1.4% in 2001. Census data is organised by country of birth as well as by ethnicity; in 2011 4,400 people born in Africa lived in Lincolnshire, making up 0.6% of the population.[1] According to data collected by the University of Lincoln Human Resources Report, 8.3% of students and 9.2% of staff identified as BME in 2016/17.[2] Numbers, however, do not tell the full story.

As Peter Fryer points out in Staying Power: the History of Black People in Britain, Black history in Britain begins with the Romans, and the soldiers, slaves, and officials who came from Africa and North Africa to this island.[3] Recent scholarly work on race in the Middle Ages shows that there is much to be said about what was once perceived as a gap in Black history in Roman period and the early modern; if you are interested in Black history in this period you may find some of the books in the footnotes below a good place to start.[4]

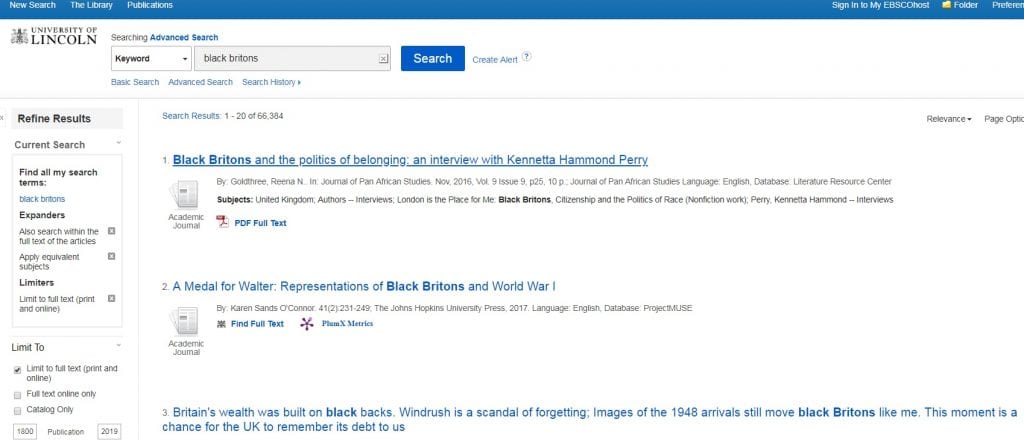

Searching, either via indexes or keyword searches within e-books, is one way to find information about Black history specific to Lincolnshire. For example, a search for ‘Lincolnshire’ in the e-book version of Fryer’s book, turns up information about a Black slave in the household of the Jenkinsons of Claxby (near Market Rasen), who was murdered by his master; and in 1680 twelve Black slaves and their families lived in Nottinghamshire.[5] You can use keyword searches such as ‘Black Britons’, ‘Blacks—Great Britain—history’ and ‘Black History’, and then filtering the Source Type to books and e-books as a way to locate other books on Black British History and the Black British experience. Keyword searches as well as the tables of contents and indexes of these books will point you towards local Black history.

Resources for Black History in Lincolnshire

Mentions and references in surveys of Black British history can be one way to locate information on Black history in Lincolnshire. In this second section of the post I will discuss a few other resources you may want to look at to find source material, including library databases, a catalogue of archival and heritage material in Lincolnshire, and two online archives.

The library databases Empire Online and Mass Observation Online both have the potential to be useful for providing contextual material on the Black experience in Britain and British Empire, although not necessarily material specific to Lincolnshire. Empire Online is a collection of primary source documents, collected from international archives, covering the history of imperialism from the late fifteenth through to the twentieth century. Its collections are into five thematic sections, and you may find Section V: Race, Class, Imperialism and Colonialism, 1607-2007, particularly useful. All sections of the collection feature thematic essays with links to primary sources of interest for the topic.[6] Mass Observation Online, a database of materials collected by the Mass Observation project which was carried out from 1937 to the mid-1950s; while the vast majority of material in the project was produced and collected by white British people, as Tony Kushner points out the database has great potential for the study of attitudes towards race and culture.[7]

The library also subscribes to a number of newspaper databases, which include digitisations of historical newspapers from the East Midlands. The British Library Nineteenth Century Newspaper Collection includes the Derby Mercury and the Leicester Chronicle; and you can use the Burney Collection, which features seventeenth and eighteenth century newspapers from the East Midlands, the Leicester Herald and the Stamford Mercury. It is worth keeping in mind that these papers were produced by white newspapermen for a white audience, and that any searching you do in them may be most successful when using historical ways of referring to race (‘negro’ rather than ‘black’, for example).

When searching for archival material relating to Black history in Lincolnshire, it is worth exploring Lincs to the Past. Designed to give access and information about cultural heritage in this county, Lincs to the Past provides a convenient search portal for the full collections of Lincolnshire County Council’s museums, libraries, and archives. It also includes a newspaper index of articles from the Lincoln, Rutland, and Stamford Mercury, and books and periodicals specific to the history of Lincolnshire.

Two other digital archives and projects may be of interest in research the Black history of Lincolnshire. One is the International Bomber Command Centre Digital Archive; the archive includes oral history interviews with those who served in Bomber Command as well as memorabilia handed down through their families. Those who served included 550 aircrew and 6,000 ground crew of African origin, and there are three oral history interviews with the sons of West African fliers, Eddy Smythe, son of John Henry Smythe; Olu Hyde, son of, Adesanya Hyde, and Neville Shenbanjo son of, Akin Shenbanjo.[8]

The other is Frederick Douglass in Britain and Ireland. Put together by Dr Hannah Rose Murray, who spoke about her work at the School of History and Heritage Research Seminar in October 2018, the site charts the lecture tours of African-American abolitionists and former slaves around Britain and Ireland during the nineteenth century. The site includes biographies of each of the abolitionists, a series of articles on Frederick Douglass’ lecture tours, and interactives maps of his tours and those of other abolitionists. The map shows that Moses Roper spoke numerous times in Lincoln between the late 1830s and late 1850s, and in Frodlingham, Gainsborough, Louth, and Brigg.

Final Thoughts

In sum, there is no one place to go to find sources for Black history in Lincolnshire, but many different places—newspapers, physical and digital archives, and books and articles in the library—which, put together can help communities, historians, and everyone who is interested in the past to tell, share, and remember these stories. As we hope this series of posts has shown, there are a wide range of resources for this research available in the library and outside of it.

Notes

[1] Lincolnshire Research Observatory, The 2011 Census. Lincolnshire County Council. Available from: http://www.research-lincs.org.uk/2011-census.aspx [accessed 26 October 2018]

[2] University of Lincoln Human Resources, Staff and Student Diversity 2013-2017. University of Lincoln Equality and Diversity. Available from https://equality.lincoln.ac.uk/ [accessed 26 October 2018]

[3] Peter Fryer, Staying Power: the History of Black People in Britain (Chicago, 2010)

[4] Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge, 2018); Lynn Ramey, Black Legacies: race and the European Middle Ages (Gainesville, 2014); and Matthew X. Vernon, The Black Middle Ages: Race and the Construction of the Middle Ages (London, 2018).

[5] Fryer, Staying Power.

[6] Douglas Lorimer. ‘From Emancipation to Resistance: Colour, Class and Colonialism, 1870-1914’, Empire Online, (Marlborough: Adam Matthew, 2007). Available from http://www.empire.amdigital.co.uk/Essays/DouglasLorimer [Accessed 2 November 2018]. While looking for material on Empire Online I came across A.B.C. Merriman Labour, Britons through Negro Spectacles, or a Negro on Britons (London, 1909).

[7] Tony Kushner, ‘Mass-Observation Archive Occasional Paper No. 2 – Observing the ‘Other’: Mass Observation and Race’, Mass Observation Online (Marlborough: Adam Matthew, 1995). Available from: http://www.massobservation.amdigital.co.uk/FurtherResources/Essays/MassObservationArchiveOccasionalPaper2. [Accessed 2 November 2018].

[8] Heather Hughes, ‘African Airmen in RAF Bomber Command’, 24 October 2017 [blog] https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2017/10/24/african-airmen-in-raf-bomber-command/ [Accessed 2 November 2018]. Other websites which may be of interest include the RAF’s online exhibition on pilots of African heritage, ‘Pilots of the Caribbean’. Royal Air Force, ‘Pilots of Caribbean: Volunteers of African Heritage in the Royal Air Force’. 2018. https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/online-exhibitions/pilots-of-the-caribbean.aspx accessed on [2 November 2018] and Cy Grant and Hans Klootwijk, ‘Caribbean aircrew in the RAF during WW2’. 2008 http://www.caribbeanaircrew-ww2.com [Accessed 2 November 2018].