This is part one of the second in a series of four posts about using library collections for the study of black history, literature and culture, in Britain and abroad. We would love to hear your comments and questions about the posts: please tweet us @GCWLibrary, email us at library@lincoln.ac.uk, or tell us your thoughts in the comments section at the end of the post.

Evidence of the lives of black people in Renaissance and early modern Europe appears in almost all kinds of texts, documents, and images surviving from these periods. For political, racial, and historical reasons this material has often been overlooked or treated as atypical and isolated.[1] This pair of post will focus on one kind of material: early printed books, by which I mean books printed between around 1450 and 1700.[2] The first part of this post will give a brief overview of our databases of early printed books and how to search them. In the second part, I’ll discuss some of the authors and issues in black history that these databases can be used to investigate.

Part 1: Early Printed Books Databases and How to Search Them

Early European Books (EEB) and Early English Books Online (EEBO) contain images of the pages of hundreds of thousands of books printed in Europe, England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and British North America between the earliest days of printing in the fifteenth century to the early eighteenth century. Issues of authorship and authority, censorship and what we would now call copyright, publication and promotion, as well as the technologies of printing and making books, all look very different from what came before or after.[3] Early printed books databases allow those who study them to track these changes over time. Some early printed books are as rare as the rarest of manuscripts, and databases can give access to material which would otherwise be very difficult to see.

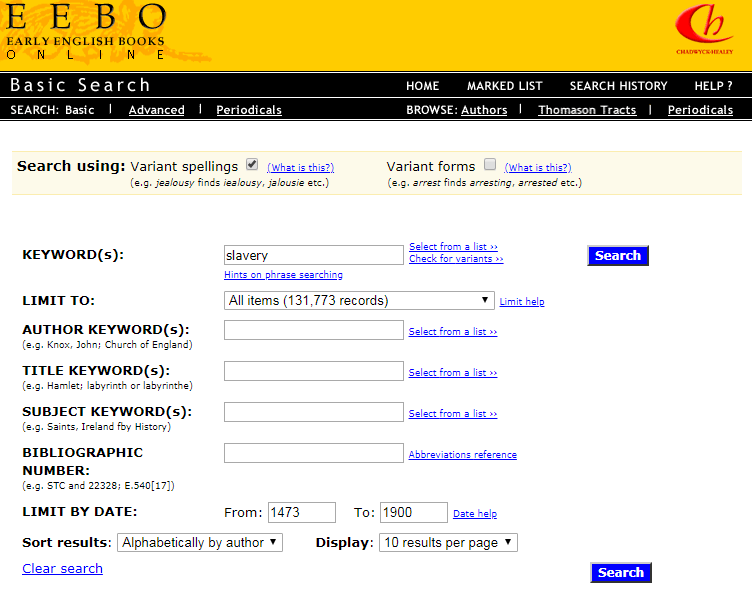

Both EEB and EEBO can be searched with a simple keyword search. For example, if you were interested in the early modern trade in African slaves, you might type slavery into the keyword search box, as below:

Particularly if you are just starting your search or are new to using EEB or EEBO, it often helps to click on the ‘select from a list’ hyperlink next to each box. This gives you a quick overview of the way information is organised within the database and helps you select the search terms that will bring up the information you need. EEBO will automatically check for variant spellings—early modern writings sometimes spell words differently to the way we do now, and different ways of spelling the same word were common. If you are struggling to find what you want to find, do check out the HELP? section for advice on how to make the most of your searches, and don’t hesitate to get in touch with your academic subject librarian. We are very happy to help.

The search interface for EBO looks a bit different but follows the same principles: you can do a basic search by keyword:

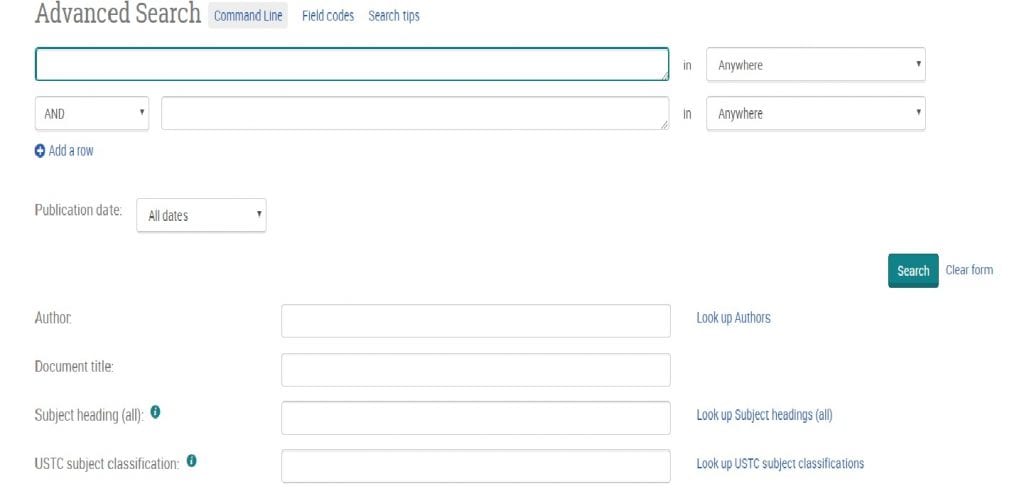

Or you can do a more specialised search for books published between particular dates, or with particular subjects, using the advanced search function:

USTC = Universal Short Title Catalogue, an important scholarly project to catalogue all European early printed books, from the earliest days of printing until the end of the sixteenth century.

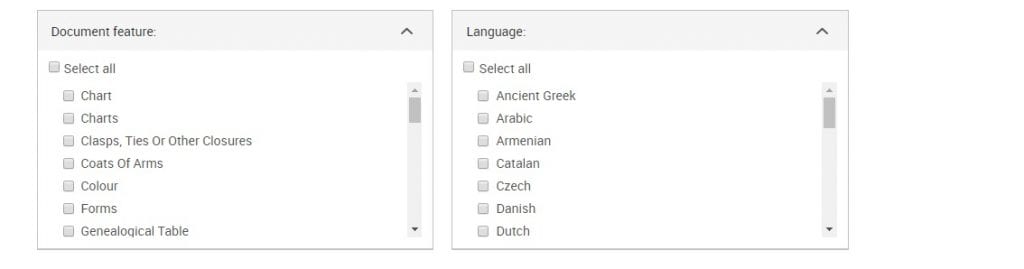

You can even (this is true of both EEB and EEBO) look for books in particular languages, or with certain features, such as illustrations or charts:

The search tips section in the basic or advanced search can be an enormously useful resource for getting the most out of searching EEB as well as understanding any unfamiliar terms. As with EEBO, looking at the databases list of subject headings can be helpful in designing an effective search and providing additional ideas for useful search terms.

In part two of this post, I will discuss some specific issues and topics in early modern Black history that can be studied through the books in these databases.

[1] Kate Lowe, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (Cambridge, 2005), 3-8. If you are interested in reading more this book is in the library collection.

[2] The earliest printed books are distinguished from ones that come slightly later: scholars call books printed before 1501 using moveable type incunabula (this comes from the Latin word for cradle and is used figuratively to refer to the beginnings or origins of something). There are many wonderful sites about the early days of printing, including the University of Manchester Library site First Impressions, http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/firstimpressions/, which contains a useful glossary of the terminology of early printed books.

[3] Adrian Johns, The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (Chicago, 1998), 1-6. This book is also available in the library collection.